Having a shorthand for a specific task or within a specific field can be helpful, time saving, and even life saving. In an operating room, it’s far quicker to tell a surgeon to get a “four-by-four” rather than to say, “Get me that gauze and make sure it’s four inches by four inches square.”

Sometimes, jargon can seem superfluous, especially when used by someone who may just want to impress you with their niche knowledge or skills. This person will probably come off as a little bit arrogant. You may even have been this person yourself at some point — it feels good to know what you’re talking about, or to have a little more know-how about something. But truly, the intent behind jargon should be efficiency, and not just to say, “Cleat that line, we have a starboard tack,” just to show off.

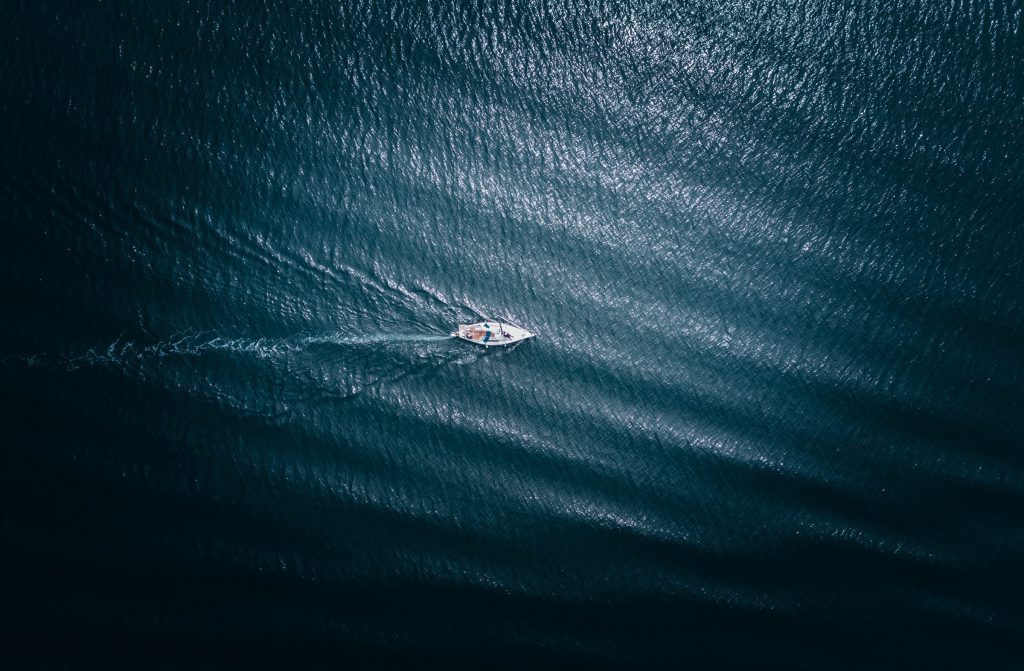

Sailing provides great examples of jargon, its usefulness, and even its questionable use cases — and you’ll no doubt notice that I used some sailing jargon in the previous paragraph.

I went sailing with a friend who not only let me know I had my “port” (left side when facing forward) and “starboard” (right side when facing forward) mixed up the whole time, but that when it’s time to “tack,” that means to brace, duck an oncoming sail if needed, “cleat a line,” and then move to the other side of the boat to help distribute weight. The ropes on boats are referred to as lines, and the cleats are what keep them in place when you want to tighten or loosen a sail.

I then realized that there is more than one type of “cleat.” My friend had referred to three metal attachments on the boat, all different shapes, so I asked, “These are all called ‘cleats?’” To which my friend, a certified sailing instructor, goes, “Yeah, I guess so.” Sometimes, things are just called things. And admitting when you don’t have all the information does make the use of jargon seem more legitimate — sometimes for ease of use, not all the details make perfect sense. To call that metal thing a cleat, and that other metal thing a cleat, won’t stand in the way of getting the job done. Calling them “small cleat” and “standard cleat” might help, but if you’re in a sailing situation, with high winds and a line that needs to be secured, you’ll know what to do and what cleat to use. Sometimes instincts and specific jargon work hand-in-hand.

Sailing is totally different from boating on a pontoon or speedboat. Sailing is hands-on: you are effectively a crew member. Sails and lines need adjusting, and the wind — which is always moving, speeding up, and changing — is your guide. Being on your toes, metaphorically and physically, is essential, and having that jargon helps immensely. But when initially learning the ins and outs of sailing, the jargon can seem like another hurdle to overcome, along with trying not to get whacked in the face when tacking (“tacking,” as an action, means to change direction of the boat, while “tack,” as a noun, refers to the direction you’re going, relative to the wind). The jargon shouldn’t be intimidating — learning a new skill requires asking questions, trying things out, and learning from those who have a bit more experience.

Jargon is a tool, and when treated that way, can be an effective, efficient, and even fun way to get a job done. But as with any tool, it needs to be used properly. When creating surveys or communicating with customers and employees, it’s crucial to avoid unnecessary jargon that will only confuse or irritate your audience. Jargon has its place, but your target audience must know what you’re talking about. Otherwise, they’ll be lost at sea — and no one wants that.

My friend and I made it back to the dock. I had helped with the sailing duties, and got off the boat knowing the difference between “jib” and “jibe.” And I won’t forget which side is starboard again.